Bicycling and books are two topics that I can get pretty excited about. So a combination of the two is sure to catch my attention.

Such an instance is an online compilation by the editors of Bicycling magazine of the 10 best books about bicycling.

Topping that list, at No. 1, is a book by a friend, David Herlihy, Bicycle: The History, which Bicycling called “a comprehensive guide to the early evolution of the bicycle.”

Topping that list, at No. 1, is a book by a friend, David Herlihy, Bicycle: The History, which Bicycling called “a comprehensive guide to the early evolution of the bicycle.”

David’s book, published in 2004 by Yale University Press, has proved to be an excellent reference for posts in this blog.

He is also the author of the 2010 book The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of An American Adventurer and His Disappearance, about which I’ve written in this blog.

Here’s what Bicycling magazine had to say about Bicycle: The History:

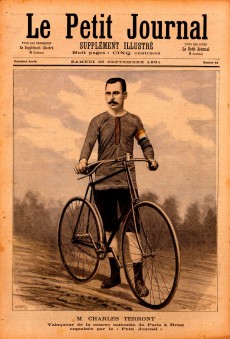

Filled with anecdotes from the late 19th and early 20th century, along with hundreds of photos, drawings and catalog excerpts, this is a book that can be consumed in bits, browsed or read with careful attention.

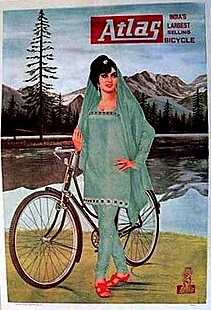

Herlihy examines not just the machines and riders, but the changes in society and the world brought about by “the poor man’s horse.” The marketing of bicycles, the role of the machine in liberating women from the confines of Victorian society, the development of paved roads, and other tales fill more than 400 pages, yet the book does not drag or feel padded.

While Herlihy’s history gives context to our current age, those looking for details on modern developments had best look elsewhere. No single book can adequately cover so broad a subject with such a long and rich history, so Herlihy has wisely chosen to focus the bulk of his energies in examining the first 50 years of bicycling.

Here’s the rest of the list of Bicycling’s 10 best books:

— The Dancing Chain: History and Development of the Derailleur Bicycle, Frank Berto

— Full Tilt: Ireland to India With a Bicycle, Dervla Murphy

— Ghost Trails: Journeys Through a Lifetime, Jill Homer

— Joyride: Pedaling Toward a Healthier Planet, Mia Birk

— Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer, Andrew Ritchie

— Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer, Andrew Ritchie

— Need for the Bike, Paul Fournel

— Park Tool Big Blue Book of Bicycle Repair, C. Calvin Jones

— Slaying the Badger: LeMond, Hinault and the Greatest Ever Tour de France, Richard Moore

— The Wonderful Ride: Being the true journal of Mr. George T. Loher who in 1895 cycled from coast to coast on his Yellow Fellow wheel, George T. Loher